March 24, 2020

Spokane, WA

My great grandfather made quite a name for himself between 1900 and his death in 1925. His factories were the largest employers in Evansville, Indiana. At one point they were the largest manufacturers of truck bodies in the world. He made gas engines and refrigerators for Sears, and leased to Sears a building for its first retail store. His accomplishments go on and on. Toward the end of his life he became quite a philanthropist, giving away three quarters of his wealth, most of which went to what is now University of Evansville.

Curiously, in all his accomplishments and no little (at least regional) fame, he seems to have never mentioned that he was born the grandson of a freed slave. He was also somewhat vague about his early adult years, other than having been in real estate and insurance in Kansas City when he was getting started. I had never much pursued that until recently. Oh, my. What a journey.

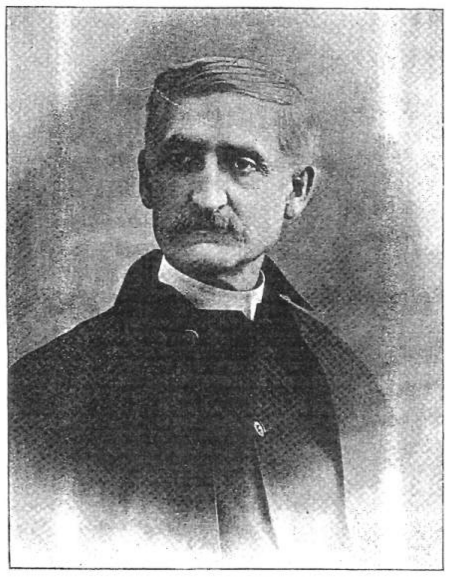

Herein, Dear Readers, I give you the story of a man my great grandfather became involved with in a highly dubious, and pretty clearly fraudulent, scheme. A man whose story is a gift as he was just one fascinating fraudster. A man named C.J. Weatherby.

Charles Jerome Weatherby was born in 1844 in Bethel, Michigan. His mother died when he was just three, and his father was a prosperous farmer who was twice elected to the state legislature. Though nothing is known of his youth in Michigan, he served only three months in Company F, 9th Indiana Infantry during the Civil War, and he appears to have served honorably and was discharged as a sergeant, along with the entire 9th, in July of 1861. He may have also been the Lieutenant Charles J. Weatherby who served just ten days in Company H of the Indiana 9th in 1963. After discharge, he married sixteen-year-old Rosa Van Tress in Mount Pleasant, Iowa in 1874.[1]

By 1878 he was publishing a small weekly paper in Hot Springs, Arkansas, styling himself “Dr. C. J. Weatherby.”[2] He would frequently claim to be a physician, and worked in that profession off and on for years, though there is no record of him having any formal medical education. To be fair, there was little formality in medical education in those days. Medical colleges did not require an undergraduate degree for admission, and few were associated with formal colleges and universities where one might expect academic rigor.[3] Indeed, there was no requirement to have a medical degree in order to practice medicine. Twenty years later, at the time of the yellow fever outbreak in Cuba during the Spanish-American War, Cuban doctors were suspicious of those trained in the U.S., as standards for medical training in Cuba were for more stringent.[4]

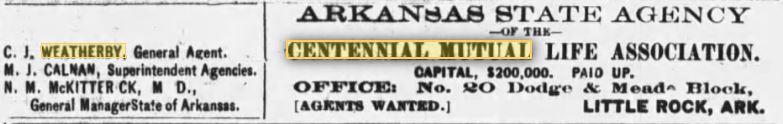

Centennial Mutual Life Association

While the secretary of the company as early as 1876, starting in 1881, Weatherby was the chief promoter of the Centennial Mutual Life Association throughout the Midwest.[5] In Kansas, Arkansas, Missouri, Nebraska, and Oklahoma, all through 1881 ads were placed in local papers for life insurance with Centennial, claiming “Five Years Unparalleled Success.” Centennial was based in Burlington, Iowa, just ten miles from where Weatherby married.

The business model, while not unique, was billed as a “mutual association.” These mutual plans were claimed to be exempt from state insurance laws, though they would come under intense scrutiny by insurance commissioners in state after state all through the 1880s.

The model was an upfront signup fee to the “association” after passing a physical exam, resulting in a certificate that promised to pay $5,000 upon the death of the policy holder. There was then an assessment to all living policy holders every time a member died. This assessment was based on the age of the policy holder, running between $0.75 and $2.50. The maximum for assessments in any year typically being seven dollars.

Full-page ads were sometimes taken out that occupied the entire front page of the paper, as in the Shelbina, Missouri, Democrat in March 16, 1881. The ads would extoll the solidity of the association, explain the moral duty of every man to provide for his family in case of his untimely death, and promote the superiority of the “mutual” model over traditional insurance. A list provided twelve reasons why this was the only logical and moral choice of a loving husband. The ads also often included a testimonial from someone who had been saved by a large cash payment, obtained from Centennial without difficulty, after the death of her husband. While these full-page ads were not common, smaller ads ran throughout the central Midwest would announce the establishment of an authorized local agent. Agents were constantly being recruited.[6]

While the company lasted at least ten years, its model was suspect. Mutual aid associations existed within numerous fraternal organizations (Woodmen of the World, Odd Fellows, etc.), but these did not take out expensive ads or sell through commissioned salesmen. These were almost always set up with a set annual payment designed to maintain a pool of money large enough to pay fixed death benefits.

What surprised many members of Centennial was that there was no guaranty of a payout at the full face value of the certificate. That certificate value was, in fact, only the maximum that might be paid. The true amount paid was the sum of the member assessments in the ninety days after the death of a certificate holder, less a 10% administration fee. If glowing printed testimonials were to be believed, happy certificate holders would be quite satisfied with their payout:

A TESTIMONIAL.

Here is a testimonial in favor of the Centennial from one of its own members, and one also who has felt the blessings this association affords to the sorrow-stricken. The letter speaks for itself.

Bedfield, Iowa, Feb, 5, 1881.

I take this method to say to the public that the Centennial Mutual Life Association, of Burlington. Iowa, has this day settled my claim fully and to my entire satisfaction.

Something over one year ago my husband and myself took out insurance in the above named co. I, like most women, was somewhat opposed to life insurance at first, but as time passed I began to consider the assessments as a fund that was blessing other homes and that at some future time would come back to bless our home.

My husband took sick on the 16th of July last, and died on the 18th, after a sickness of but two days. I was left with a family of seven small children; our little home had an incumbrance of nine hundred dollars which we never could have paid without insurance; better than all, I am now able to keep my family together. After clearing our little home of all incumbrances and paying all mv personal debts, I will have about nine hundred dollars to place at interest for the benefit of my children. I look upon the Centennial as the best friend to the poor and take pleasure in recommending it to the public.

Mahala A. Coulter.[7]

Others, however, collected only a few hundred dollars. By only paying out what it was able to collect via assessments, Centennial assumed no risk whatsoever. The claim of “Capital $200,000 Paid Up,” was highly misleading. In was made to sound like this was a bond with the state that would guaranty payment to policy holders, such as legitimate insurance companies were required to have. In reality, it was to back up payment of the policy as written, which only required Centennial to pay what it could collect in assessments. In other words, it was meaningless.

Weatherby worked for Centennial for some years, and the company went on without him after he left. However shady its business practices, it stayed out of trouble with the law.

Royal American Graveyard Benefit Association

If Centennial was a questionable business model, Weatherby’s next venture, the Royal American Graveyard Benefit Association was his first, if certainly not last, outright fraud. Set up in Indianapolis in January, 1883,[8] it was driven out of that state by April due to bad press and the threat of fraud charges. When it set up in Topeka in April, Weatherby was in charge.[9]

The company didn’t even last a year in Topeka. So obvious was its fraud that the Leavenworth Times hounded it with unrelenting bad press. It was, like Centennial, a mutual life insurance scheme, but its structure was purely fraudulent. Policies of $1,000 could be taken out, up to five on any one individual. The person being insured didn’t even have to know the policies existed, so no physical exam was required. Astoundingly, no one under the age of sixty could be insured. Again, death payments were based on assessments to current policy holders, but this time the company’s administrative fee on payouts was a whopping 33%.

The largest red flag was the suspicious requirement for the insured to be over sixty. Any legitimate life insurance plan wants to spread the risk of payments to policy holders across a large pool of younger policy holders. But Royal American profited handily when someone died, as they got their 1/3 cut. No sooner had Royal American set up in Topeka, then The Leavenworth Times began writing scathing pieces about the company. Under the banner “The Graveyard Ghoul,” the Times pointed out that even though the policies were written to not pay in the event of murder, the business model actually encouraged it. Royal American threatened to sue for libel, but there was nothing libelous about it. The company folded by the end of 1883.[10]

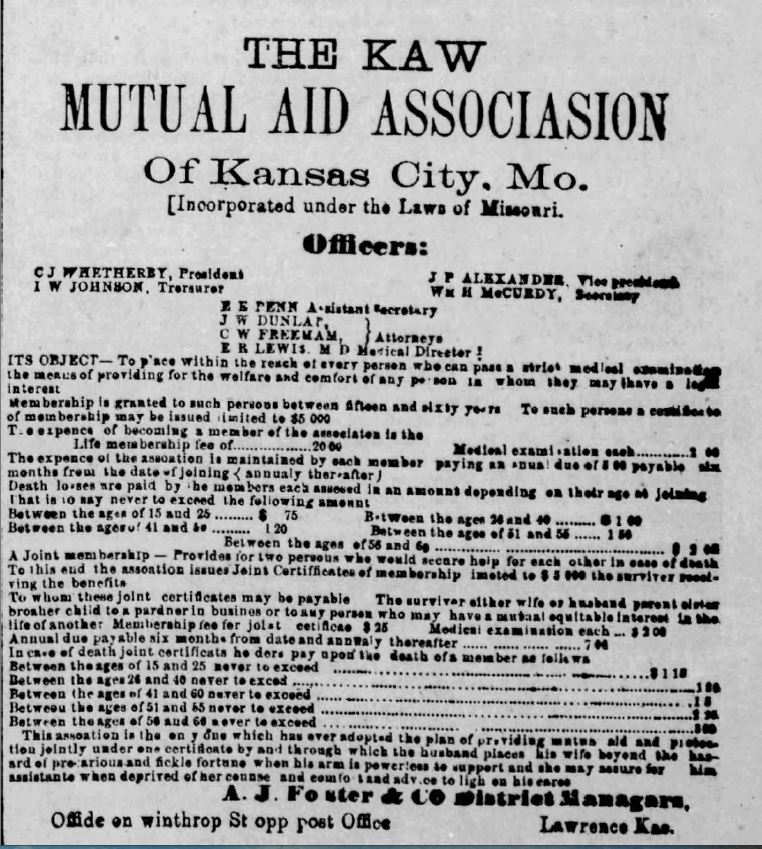

Kaw Valley Mutual Aid Association

Weatherby, however, was not to be deterred. While still styling himself as a doctor, he clearly believed there were more riches in insurance than in medicine. If you couldn’t cure them, you could at least profit from their death. He just needed to perfect his business model. Perhaps if he could meld the usurious 33% commission on death payments with the more sustainable Centennial model, then he might have a winning model.

He must have seen the writing on wall with respect to Royal American, as even before its final demise, he was involved in setting up the Kaw Valley Mutual Aid Association. Though the name was an appeal to Kansans, the firm was originally incorporated in Kansas City, Missouri, with Weatherby as president, and Wm. H. McCurdy as secretary. Anyone having read the full front-page ad for Centennial in the Shelbina Democrat just over two years earlier, would easily recognize another full front page ad, this time for Kaw, in the Fort Scott Daily Monitor in May of 1883.[11]

The same appeal to a man’s sense of duty to family, the same talk of “unparalleled success,” and the same exact list of twelve reasons why someone should join. This time, however, it included a long, multi-column, highly flowery story by a woman who had once scorned insurance. She had refused when her husband suggested it. Then their idyllic life was destroyed when he died suddenly, leaving her with debt and two hungry children. Referring to her husband’s previous attempt to buy life insurance, she writes:

O! how I have looked back on that unhappy evening, when he, burdened with a sense of what might befall us, longing for nothing so much as the happiness of those loved, came to me with such a royal gift. And through these dark years, when my pen has been the only means of my subsistence, my husband never appears so unselfish, so manly, so magnanimous, as when on that night he sought to secure me the certainty of a competency in case he should be taken off. Had I allowed the policy to exist, would I have regarded it as blood money? No! It would have been love money—a token of this pure unselfish affection. And it required no reason to bring me to this conclusion. I saw it at a flash, on looking at my destitute condition.

The plan was almost identical to Centennial, only with Royal American’s fee structure. A $5,000 “Certificate of Membership” (carefully avoiding the word “policy” which might trigger scrutiny from state insurance commissions) could be had for an upfront membership fee of $20, and medical examination fee of $2, yearly dues of $5, and assessments for other members’ death according to the age of the certificate holder.

Unlike with Royal American, they apparently did not insure anyone over sixty. The maximum paid in yearly assessments was $7.20. “Experience has proved that assessments are light,” Kaw’s ads explained, “and that the poorest man is enabled to provide for his family and secure them from want and dependence.”

With the benefit of hindsight provided by historical records, we can see how flawed the model was, even assuming it intended to be legitimate, which it almost certainly did not. While rural areas had lower mortality rates than cities, statistics from St. Louis in 1880 are illuminating. That city had an overall all-cause mortality rate of 6.48 deaths per 1,000 residents that year.[12] Kaw paid out not based on membership fees or dues, but on assessments paid by living members. For every 1,000 members, the maximum collected per year would be $7,200, but those same 1,000 members would see six and a half deaths. Once Kaw took its 33% cut, the $7,200 pool would dwindle to $4,752, divided by six and one half, that would mean about $731 paid per certificate holder death, if every living member paid each assessment in full. That’s a far cry from the $5,000 most policy holders expected. As we shall soon see, payment of member assessments was paltry.

By early 1883, the state of Missouri had deemed Kaw (and other similar schemes) to fall under the purview of the insurance commissioner and a bond would have to be posted with the state. No amount of “paid up” capital would suffice. Kaw immediately moved across the river and set up shop in Kansas City as well as Leavenworth, Kansas. The advantage of this move was short-lived. By the end of June, 1883, the Kansas State Circuit Court at Leavenworth ruled that Kaw, as well as Independence Mutual Aid Association, even though registered as mutual benefit associations, were nothing other than regular insurance companies. The court order the two associations to be dissolved.[13] Undeterred, and perhaps realizing that there was no place to run where they could avoid insurance regulation, Kaw immediately reincorporated as an insurance company in July, filing bond with the state for $50,000.

In order to help pay for their bond, however, and generally to generate more cash, the business model changed. The membership fee was now $34 and the dues were gone, but a fee of $50 in four equal payments was required before the policy was considered valid. None of that $234 went to pay death benefits, which were based purely on member assessments.

To show the solidity of their organization, they ran ads such as the following:

This is to certify that on the 27th day of December, 1882, my husband, Geo. W. Brady, of Paola, Kansas, secured a certificate of membership in the Kaw Mutual Aid Association, of Kansas City. He was then a strong and healthy man, but we must all die. He lived only five months, passing away on the 26th of Sep, 1883. The proof of death was received at the office on the 6th of June and on the 7th of July I was notified to call at the office in Kansas City. I did so and received my money in full, according to contract. I wish to say that the Association has dealt honorably with me and has proved a great blessing in an hour of need. Henrietta Brady.[14]

As it had done in April, the Leavenworth Times began to attack the company, tying its president, C.J. Weatherby, back to the failed fraud of Royal American, stating “It is a fraud of the first water, and we hope none of our friends will be foolish enough to take any stock in it. We do not believe it can do any business in Kansas.”[15] Even local citizens paid to run their own warnings in the press, “I wish to warn all persons against having anything to do with the Kaw Valley Life Insurance Co, for they are not good for their contract. J.H. GODDARD,”[16] Goddard, a physician, obtained a judgement against Kaw for $25 – likely amounting to only what he had paid in so far.[17]

In 1884 and early 1885, papers all over the state ran pieces critical of the mutual insurance model in general, and Kaw in particular. Accusations were that Kaw did anything it could to find fault with a policy claim (such as unpaid assessments), or often negotiated that payment to the minimum possible. Reports were that assessments were often unpaid, though that brought no risk to Kaw, only to those claiming payment on a policy. By the end of 1885, things were looking grim:

After spending from $50 to $175 on insurance in the Kaw Valley Life Insurance Co. the great majority of the policy holders of that institution in this vicinity have given it up. The trouble seems to be that too many sickly persons were taken into the organization, and these dying the assessments were piled up beyond endurance.[18]

By the following January, Kaw called it quits. They withdrew the deposit for their bond, announcing they would refund the initiation fees of current policy holders, but would pay no more benefits. While no laws had apparently been violated, the company, or its management who had posted the required bond, were susceptible to civil suits. By September, though no longer in business, the lawsuits against Kaw made it untenable for its management to stay in the state. On September 24th, the Empororia Weekly reported that Weatherby and McCurdy had fled that state and the company’s books were missing.[19] If out of state, no state court civil award against the absconded manager could be collected. The life and death of Kaw was nicely summarized by the Minneapolis Messenger:

The Kaw Valley Mutual Life Insurance Association began business in the state of Missouri, but the rigid enforcement of the excellent insurance laws of that state compelled it to move. It opened up in Kansas, where the laws were very lax. The amendments made to the Kansas insurance laws within the past two years have made them better, and compelled a number of bad companies to quit business. The Kaw Valley put up the necessary bond and endeavored to do business, but has always been looked upon with some suspicion. Last week the president mysteriously disappeared. Some of the remaining officers have reorganized, but we would advise a thorough overhauling by the insurance department before it be permitted to do more business.[20]

It is interesting to note that, years later, Kaw was seen only as a business that had failed due to unforeseen circumstances. Though we shall see that Weatherby continued to be involved in sketchy schemes, at least two former executives from Kaw went on to build solid reputations as businessmen. Wm. McCurdy built an impeccable reputation as a manufacturer and business leader in the early 1900s, and an obituary said Ryerson Hilliker ran a successful manufacturing company, and was elected mayor of Kansas City, Kansas.

Upon fleeing Kansas in 1886, Wm. McCurdy moved his family of six to Cincinnati where he became employed as secretary of the Favorite Buggy Works, a firm owned by his father-in-law, Alfred Hess. A generous interpretation might be that Hess recognized McCurdy’s skills at running a business, but it would not seem inappropriate to suspect that he was more concerned with his daughter and four grandchildren having a means of support. Another generous interpretation would be that McCurdy was simply the unwitting dupe of a slick con artist, but he would have had to be a fool not to have seen the newspaper articles clearly tying Weatherby to the fraud of Royal American.

On to Fraternity

While there is no indication that Wm. McCurdy ever saw Weatherby again, it would be an historical injustice to leave Weatherby’s story here, half told. He was far from done with insurance schemes, though took a break from it from 1887-1890, setting up shop first in Hot Springs, Arkansas, then in St. Louis as a physician. The only indication of impropriety here is an odd court case in 1889 where Weatherby is not accused, but where it is documented that he was paying a “drummer” $5 per medical patient referred.[21]

He didn’t last long as a physician, however. From 1891 to 1893, he lived in Salt Lake City, Utah, working selling mining equipment, real estate and, of course, insurance. It was here that he must have dwelled on his past insurance schemes and why they had failed.

What had been the death knell of Kaw had been declining membership. According to a post-mortem conducted by the Kansas State Insurance Commissioner, Kaw reported 3,923 members for 1884, 2,377 for 1885, and only 197 for 1886.[22] So how could an insurance company keep members, and thus assessments, from declining? What would induce people to stay with the organization?

The answer was all around him. In the latter quarter of the 19th Century, fraternal organizations flourished, and many new ones were created annually. Many of these had an insurance aspect to them, but all had something else: a unifying them that created a desire of their members to belong that didn’t rely entirely on insurance. Many would go on to become well-known, even if not very common today. The Independent Order of Oddfellows, the Knights of Pythias, Woodmen of the World, etc. Some are still recognizable: the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks, the Fraternal Order of Eagles, Moose International, etc. The Grange, founded in 1867, still had membership of 160,000 in 2005. One of the largest of these was the Free Masons, which had first become active in this country in the 1730s.

Enter the Kassidean Knights

As early as 1888, while living in Missouri, Weatherby teamed up with an old Iowa acquaintance Edward A. Guilbert to create the Ancient Order of Kassidean Knights, clearly fashioning it on Free Masonry. Guilbert, a physician and 1847 graduate of Rush Medical College, had been a Mason since 1851.[23] Guilbert seems to have been a legitimate character and may well have simply wanted to have his own fraternal association.

The Kassidean Knights were organized in “priories” locally, and had local officials with august-sounding titles like Senior Senechel, Junior Senechel, Sarcerdos, and Senior Vigilante. The organization claimed to be a revival of the Chasidim, or “Knights of the Temple of Jerusalem.” Just as in masonry, there were three levels of members (outside leadership roles), Neophyte Kassidean, Associate Kassidean, and Knight Companion. Guilbert was styled the Grand Hierophant, with Weatherby as the Vice Grand Hierophant.[24]

When Weatherby moved west to Salt Lake City, in addition to whatever legitimate enterprises he may have been involved in, he travelled extensively in western states, trying to start up new priories of the Kassidian Knights. If a group of men could be recruited, initial dues was paid and that would go to the national-level society which, at its next annual convention, would vote to accept the local priory. As simple and seemingly common as this was it that day and age, it came under scrutiny in several places.

In September of 1889, he was charged in Sonoma, California for fraud. When interviewed by a reporter for the Sonoma Democrat, the well-dressed Dr. Weatherby was seated comfortably in the sheriff’s private office, smoking a cigar. He claimed, in addition to the Grand Chapter, priories in Fresno, San Francisco, Santa Clara, San Jose, Seattle, and Portland. He assured the reporter that the local priory, from which funds had been collected, would be accepted at the next annual meeting of the Grand Priory. The case was dismissed.[25]

There is no documentation that the Kassidean Knights had any insurance aspect to it, though it’s tempting to believe it did. Whether it was because the Kassideans were not taking off, a desire for a more lucrative scheme, or some idea that he could do better on his own, Weatherby left the Kassideans to start what would become his greatest scheme.

Knights of the Ancient Essenic Order

In founding the Knights of the Ancient Essenic Order (KAEO), Weatherby created an organization that was so successful, it outgrew him and he was eventually pushed out.

This time the plan was pure Weatherby, designed from the start by him alone, and this time there definitely was an insurance aspect. In addition to dozens of newspaper articles, two key sources give us a rich understanding of the Knights. The first is in Weatherby’s own writing, as he published a pamphlet The Knights of the Ancient Essenic Order and Their Secret Rituals. The most detailed source, however, are notes from a federal court case in Salt Lake City which includes copies of a number of documents in the formation of the Knights.

Before settling in Salt Lake City and formalizing the K.A.E.O, Weatherby continued to travel the west perpetuating insurance schemes. After leaving California, an article in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer has him making his home there in August, 1890.[26] By the following January, he was promoting the Knights in Hailey, Idaho.[27] While there is no direct evidence of Weatherby’s time in Oregon, an article in the Salem Statesman-Journal, written after his later arrest in Utah noted “The Salem camp of the A. E. O., to the number of about forty, would be glad to see Dr. Weatherby—in some penitentiary.”[28] He appears to have been starting local groups of Knights while having no legitimate organization.

By late 1891 he settled in Salt Lake City. Here he must have spent quite some time figuring the details of how to construct a national organization for the K.A.E.O. What emerged was no hacked together scheme, but a carefully crafted plan, down to the smallest details. And, of course, life insurance was a key part of it from day one.

Weatherby hatched the scheme with three others, but it was clearly his plan. In March of 1891, they formed the Utah Grand Council of the K.A.E.O., that being the state body of the organization. They also formed the Supreme Grand Senate as the national level organization. He had already organized a local “Senate” in Ogden. Weatherby, together with A.J. Varney, Earl D. Gray, and D. Van Buskirk were the grand council. They all signed an agreement where all proceeds from the organization were signed over to Gray, as he was the one fronting the cost of the organization. Gray then signed a document giving ¼ interest in this income back to each of the founding members, thus creating two levels of indirection should anyone try to sue.

And what income might this Grand Council have? The documents noted specifically mentions:

Membership fees or Initiatory fees accruing from the organization of all senates throughout the jurisdiction of the Supreme Grand Senate K.A.E.O. also all fees accruing from the issuing of dispensations, charters, certificates of insurance, all per capita taxes, all amounts charged and collected, from the Senates or initiations together with all sums that may be charged as commissions, or reserved from the collections of mortuary assessments or fees, also such amounts as may be charged as reinstatements, also annual dues and interest accruing from reserve fund when regularly credited the contingent or expense fund. In fact, all that may be received from any and all sources of the Supreme Grand Senate K.A.E.O.

For a fraternal organization, clearly a lot of thought had gone into sources of revenue. All of this went first to Gray, then was distributed to the four founding members.

But the success of Weatherby’s schemes had always hinged on getting members to pay death assessments. Royal American and Kaw had failed as not enough “members” were willing to pay. This time, it would be different. Weatherby’s undated The Knights of the Ancient Essenic Order and Their Secret Rituals comprises over fifty pages of elaborate ceremonies and rituals, all steeped in ancient wisdom, mystery, and a lot of really silly pageantry. In addition to three standard levels of membership (identical to the Kassideans and to Free Masonry), there were numerous offices in each local senate, include Grand Senators, Junior and Senior Senaschals, Junior and Senior Vigilantes, and a Surgeon. Later, as the organization grew, Weatherby would add a military aspect, the Essenic Army, with lofty military ranks. By bonding members to each other, with formal oaths of fealty to the organization, how could members not pay death assessments when called to do so? How could any man betray a fellow Knight?

It is interesting to note that these “secret” rituals, published by Weatherby, include instructions that “The Rituals of the Order are to be kept locked up, and must not, under any circumstances, be carried by members, or distributed to them by the Excellent Senator, except during the session of the Senate.”

But money could also be made, if indirectly, by selling supplies to members and to the organization itself. Reports indicated that regalia (“very nobby uniforms, swords and belts, etc.) were purchased on credit and sold to members by the Supreme Grand Council.[29] The money paid out to the four founding members was net, after expenses paid by the organization. But Weatherby had a scheme there, as well.

One of the largest expenses was printing. Ceremonies had to be documented, promotion within the K.A.E.O. required certificates, forms of all type were used for regular recording of activities, and, of course, insurance policies had to be printed, as well. It should come as no surprise that in April, 1892, the Ackerman Printing Company incorporated in Salt Lake City with thirteen owners including Weatherby, his wife, his mother-in-law, and Earl. D. Gray. Weatherby and his relatives owned a 31% stake in the company.[30]

Weatherby also began publishing a formal monthly magazine for the K.A.E.O. called The Knight’s Review, printed, of course by Ackerman. In fact, the initial edition was published just six weeks after Ackerman was incorporated.

The life insurance aspect was identical to his previous schemes, though with even higher profits. After up front membership and insurance fees were paid, death benefit claims were subject to a 25% deduction for the “Reserve Fund,” and another 10% deduction for the “Expense Fund.” Both these funds were simply fancy names for profits to be paid to the founding members.

That Weatherby saw this as a money-making scheme need no further evidence than the fact that he attempted to sell half his interest in future revenues for $750. The sale was actually made, in writing, but the buyer changed his mind and Weatherby returned the money.

The reason we know all this detail is that Weatherby and Gray were arrested in late July, 1892, and charged in federal court with mail fraud. A disaffected ex-member complained to the post office that this was a fraud, and that the K.A.E.O. was conducting this fraud using the U.S. Post Office. The case caused sensational headlines for months, and both men were denied bail during the proceedings. While evidence presented, including contracts between the founding members, is still around, no actual court proceedings were recorded, or at least none now exist. Both men were eventually acquitted.

The acquittal is a testament to Weatherby’s prowess at perpetrating these schemes. Kaw had been unsuccessfully sued in court in Kansas. Weatherby had been arrested in both San Jose and Sonoma, yet never formally charged. And now his K.A.E.O. scheme had survived in federal court. It seemed rather clear to everyone that it was sleazy, but he carefully managed to always make it look like just a poorly formed business, never an outright fraud.

In creating such an elaborate organization, however, Weatherby created something that grew by leaps and bounds, eventually getting large enough that he was forced out. Within just a few years, numerous states had their own state-level K.A.E.O. senate, supporting dozens of local chapters. And Weatherby continued as the Supreme Ruler, with the additional title of “General” of the “Essenic Army.” And when traveling, a Supreme Ruler need to do so in style. When he traveled to Savannah in early 1896 to establish a Grand Senate in Georgia, he stayed at the posh De Soto Hotel.[31]

Later in 1896, there was a national meeting in Louisville, Kentucky, by then the national headquarters for the K.A.E.O. Attendees came from Mississippi, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Louisiana, Ohio, and Indiana. Local papers recorded a parade of over 1,500 members, including several bands.

Its growth led to changes, however. There were continued concerns about member fees. In May of 1897, the Supreme Senate met in Nashville for the purpose of revising the national constitution and bylaws.[32] By early 1898, the Cincinnati Post reported under the headline “Weatherby Deposed”, “The Essenic Knights Tuesday afternoon abolish the office of Supreme Ruler of the World thus deposing C. J. Weatherby. The duties were placed in the hands of the Supreme Senator W. Johnson, of Covington.”[33] And, with that, Weatherby’s associate with the K.A.E.O. came to an end.

Weatherby never again saw the glory of his years as Supreme Ruler. He seems to have separated from his wife by 1900. From 1901-03 he was the general agent for The Masonic History Co, of Biloxi, Mississippi, a publisher of bibles and Masonic books. He and his son both worked for a poultry farm in Houston in 1911, where he later worked as a notary, sold real estate, and was also listed as an insurance agent just before his death in 1916. He simply never gave up on what he knew best.

The K.A.E.O. flourished for several more decades after ousting Weatherby, then declined slowly, with the last known senate closing in 1935. In 1920 it finally revised its bylaws, changing at last into a true fraternal order. Like many similar fraternal organizations, its death was more from decreasing membership than with financial mismanagement. The organization Weatherby started in Salt Lake City in 1892, lasted over forty years and, in the end, outlived him.

But his story lives on, entertaining history buffs sitting at home social distancing from COVID-19, and maybe a blog reader or two. If this is half as fun to read as it was to research, thank C.J. Weatherby.

[1] The Free Press (Mount Pleasant, Henry, Iowa), September 1, 1874.

[2] Shelby County Herald (Shelbyville, Missouri), August 7, 1878, p4.

[3] Joy Williams. “Medical Education in America: Rethinking the training of doctors,” The Atlantic, June, 1910, 23.

[4] Molly Caldwell Crosby, The American Plague (New York: Berkeley Books: 2006), 90.

[5] The Courier (Waterloo, Iowa), May 17, 1876, p8.

[6] Shelbina Democrat (Shelbina, Missouri), March 15, 1881, p1.

[7] Shelbina Democrat (Shelbina, Missouri), March 2, 1881, p1

[8] The Indianapolis News (Indianapolis, Indiana), January 10, 1883, p1.

[9] The Leavenworth Times (Leavenworth, Kansas), April 15, 1883, p1.

[10] The Leavenworth Times (Leavenworth, Kansas), April 15, 1883, p1.

[11] Fort Scott Daily Monitor (Fort Scott, Kansas), May 15, 1883, p1.

[12] Department of the Interior, Census Office. Report of the Mortality and Vital Statistics of The United States, 1880 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1886), 23.

[13] The Girard Press (Girard, Kansas), June 28, 1883, p2.

[14] The Miami Republican (Paola, Kansas), August 10, 1883, p3.

[15] The Leavenworth Times (Leavenworth, Kansas, September 26, 1883, p1.

[16] The Sedwick Pantograph (Sedgwick, Kansas), July, 1884, p1.

[17] The Sedwick Pantograph (Sedgwick, Kansas), August 1, 1884, p1.

[18] Colony Free Press (Colony, Kansas), November 18, 1885, p3.

[19] Empororia Weekly Republican (Empororia, Kansas), September 30, 1886, p3.

[20] Minneapolis Messenger (Minneapolis, Kansas), October 14, 1886, p7.

[21] State of Arkansas. Reports of Cases at Law and in Equity, 1879. (Little Rock: Arkansas Union Printing Company, 1881), 556.

[22] State of Kansas, Eighth Annual Report of the Superintendent of Insurance, 1887. (Topeka: Kansas Publishing House, 1888), 24.

[23] http://www.homeoint.org/photo/g/guilbertea.htm

[24] State of Kansas, Ninth Annual Report of the Superintendent of Insurance, 1889. (Topeka: Kansas Publishing House, 1888), 52.

[25] Sonoma Democrat (Sonoma, California), September 28, 1889, p1.

[26] The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, August 31, 1890, p9.

[27] Wood River Times (Hailey, Idaho), January 20, 1891, p3.

[28] Statesman-Journal (Salem, Oregon), October 8, 1892, p4.

[29] The Salt Lake Tribune (Salt Lake City, Utah) August 1, 1892, p8.

[30] Salt Lake Herald (Salt Lake City, Utah), October 1, 1892, p3.

[31] Morning News (Savannah, Georgia), March 11, 1896, p6.

[32] St. Louis Globe-Democrat (St. Louis, Missouri), May 14, 1896, p9

[33] Cincinnati Post, April 27, 1898, P7.